Shirley Chisholm Is a Verb! by Veronica Chambers, illustrated by Rachelle Baker

Shirley Chisholm Is a Verb!

written by Veronica Chambers, illustrated by Rachelle Baker

You know the feeling you get when you hear the ice cream truck coming? The anticipatory thrill, the bounce-on-the-balls-of-your-feet excitement when you hear the music from down the street? That’s how I’ve felt while waiting to get my hands on this week’s book!

Shirley Chisholm Is a Verb!, written by Veronica Chambers and illustrated by Rachelle Baker, brings the vibrant boldness of its subject to every page. Even the warm mustard endpapers signal the energy, the vitality of her story. Chambers and Baker deliver a picture book biography of Shirley Chisholm that is every bit as action-oriented as she was.

The daughter of immigrants from Barbados and Guyana, Shirley Chisholm was born in Brooklyn, New York, and grew up to become the first Black woman to run for U.S. president. Chisholm was a voracious reader who earned academic honors in high school as well as college scholarships. She graduated from Brooklyn College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1946 and earned a Master of Arts in education from Columbia University in 1952. Chisholm, an early childhood educator, ran for a seat in the New York State Legislature in 1964 and won. She served until 1968 when she ran for the U.S. House of Representatives and won, becoming the first Black woman elected to Congress. Her campaign slogan in that race, “Unbought and Unbossed”, became the theme of her 1972 campaign seeking the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Chisholm served in Congress until her retirement in 1983 and was a founding member of both the Congressional Black Caucus and the Congressional Women’s Caucus.

Shirley Chisholm was a doer, an activist who broke barriers and sought to improve conditions for families and communities. Veronica Chambers introduces Chisholm to new audiences by capitalizing on her life of action, “Some words, when they connect with the right people, become…magical. That’s the way it was with Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm and verbs. She understood, almost intuitively, how and why verbs are not just words about being, but doing. Verbs are words that move the world forward.”

On each page, Chambers highlights a portion of Chisholm’s life, highlighting in color and capital letters a verb related to the brief text. The verbs anchor each page’s main thought, illustrating its point as effectively and vibrantly as Rachelle Baker’s artwork does. Chambers chooses her verbs carefully, and they offer a fantastic starting point for further conversation. They follow Chisholm on her life’s journey and, in addition to obvious choices (dreamed, campaigned, represent, voted, announced, inspired) the verbs reflect her rich experience (honor, listen, earned, help, challenge, convince, planted, pave). Chambers ends the book with a powerful two-page spread showing a portrait of Chisholm paired with a page full of verbs each in a different, brightly-colored font. In it, she issues her readers a challenge, “Shirley Chisholm accomplished so much, because she chose her verbs carefully…It’s your turn now. What verbs will you choose?”

Rachelle Baker captures Shirley Chisholm’s energetic spirit in brightly colored illustrations which give off a feeling of motion on every page. Rich browns and tans ranging from caramel to mahogany to ebony join with piercing blues, lush greens, mustard yellows, and lively oranges to form a palette of saturated colors bursting with activity. Baker’s art pulls you in as you read. On the page highlighting a famous Chisholm quote, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair”, I could almost hear the chair dragging across the floor as she pulled it behind her. I caught myself looking twice to see if her hand really did wave to her neighbors outside the corner store. Baker created her art digitally on an iPad Pro with spectacular effect so that it lives and breathes and moves on the page.

Shirley Chisholm Is a Verb! opens the door to an unexplored chapter of American history. It’s a catalyst for important conversations about representation, perseverance, service, and inspiration. It would be a great read-aloud for pre- and early-readers while independent readers might enjoy it on their own. I couldn’t wait to read this book, and it was well worth waiting for–I hope you have a chance to read it, too!

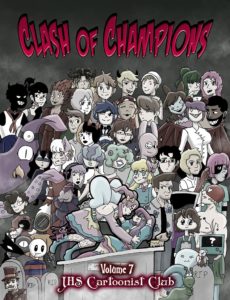

This was almost the shortest book review submitted here: “Read them! They’re wonderful!” Because that’s all you really need to know about the books published by the Joplin High School Cartoonist Club.

This was almost the shortest book review submitted here: “Read them! They’re wonderful!” Because that’s all you really need to know about the books published by the Joplin High School Cartoonist Club.